Newsletter Takeover: Feminist Food Journal

FFJ Editors Isabela Vera and Zoë Johnson share some insights from their MILK issue and a reflection on the Sourced x Wellcome Stories 'Milk, From Ground to Glass' series

When Feminist Food Journal reached out to share their thoughts on our Milk season, we were so excited to share them with you! In this free newsletter FFJ founding editors Isabela Vera and Zoë Johnson look at their MILK issue and our collaboration series with Wellcome Collection Stories.

If you’d like to read more on Milk, check out the photo essay chronicling cheese makers in central Mexico from cheesemaker Mercedes Moreno and photographer Alexander Pomper on the website now.

Hi there,

Welcome to Feminist Food Journal’s Sourced Journeys takeover!

Feminist Food Journal is an online magazine and podcast dedicated to feminist perspectives on food, politics, and culture. Our first issue, MILK, was published in February 2022. We’ve since published five more – WAR, SEX, EARTH, CITY, and SEA – and while it’s not generally considered kosher to have a favourite child, we’d be lying if we said that MILK wasn’t ours.

This is not only due to fond memories of our amateur yet enthusiastic attempts to cobble together a magazine, but also the breadth and creativity of the pitches we received – on everything from breastfeeding in the 17th century as a form of cannibalism to food fiction set in a suburban supermarket – and their links to just about all of our interest areas. Milk is at once an essential bodily fluid, a good source of calcium, a contested political signifier, a religious marker, and a global commodity. It is deeply intertwined with power and resistance. The opportunities to dig into it from feminist perspectives are endless, and we wished we could’ve commissioned more than the six talented writers we ended up working with.

We were therefore beyond thrilled to see our friends at SOURCED recently launch a story series, Milk, From Ground to Glass with Wellcome Collection Stories, as well as their own Milk season. The resonances between some of the pieces were striking and insightful. This newsletter is an opportunity to reflect on our MILK issue and the fresh work that it has been put into conversation with.

Feminist Food Journal’s MILK Issue

Letter from the Editors | Isabela Vera & Zoë Johnson

A Treasure for My Daughter | Isabela Vera

Conversations on Women and Cheese | Zoë Johnson

Got Hormones? | McKenzie Schwark

Isis, the Goddess of Milk | Adhiambo Edith Magak

The Childless Mothers | Lauren Gitlin

The Future of Cultivated Milk | Ingrid L. Taylor

The Myth of Feminizing Soy | Julia Norza

Milking Bodies to Make a Nation | Apoorva Sripathi

On the "Unbearable Whiteness" of Milk | Isabela Vera

In our Letter from the Editors accompanying MILK’s publication, we wrote (somewhat grandiosely):

Milk is used to usher in people who are like us, and separate people who are like them; it justifies hierarchies within and between human and animal, it nourishes life and it inflicts pain. Milk speaks to the past and the present, the permeability of progress and regression, to the dark edges of history and to promises of a shinier future.

In our view, this framework still stands, and it is exciting to see Wellcome Collection’s Milk stories and SOURCED pick up on some of these themes.

Agriculture, land, and change

One issue we didn’t have the chance to cover in-depth is that of land use and dairy farming. With regards to milk production, however, we looked at the tensions between loving animals and milking them (around the MILK launch, Astra and Sunuaura Taylor’s stunning essay, Our Animals, Ourselves: The Socialist Feminist Case for Animal Liberation, aptly noted how milk is both a noun and a “verb that means to exploit for profit”). This was done mainly through two pieces, The Childless Mothers, written by Vermont goat farmer and skyr maker Lauren Gitlin, and Conversations on Women and Cheese, a series of interviews by editor Zoë with three women cheesemongers from Europe and the US. We also spoke about how industrial milk production, promotion, and consumption are inextricably tied with racist, capitalist, and (neo)colonial systems of oppression in our podcast episode On The Unbearable Whiteness of Milk. Here, anthropologist Alice Yao and editor Isabela discuss the links between milk consumption and Western imperialism, particularly how the framing of “lactose intolerance” problematizes what is actually the reality for most people in the world and sets the basis for milk consumption to become a symbol and tool of white supremacist movements.

SOURCED and Wellcome Collection Stories series pick up on the implications of dairy production for land and landscapes. Three pieces deal explicitly with the impact of large-scale dairy farming, particularly with regard to Indigenous land rights. In California, the draining of the formidable Tulare Lake to in part make way for industrial dairy “was a final colonisation of my people”, writes Cecilia Moreno of the Tachi Yokuts people in How Californian dairy farmers stole a way of life. Continents away in Aotearoa, Sarah Hopkinson reflects on her family’s settler history and how the Māori land around her has been changed by their dairy farming. She writes:

I can see my Uncle Dave, a dairy farmer, a bloody good one too, getting hurrumpy. ‘I am doing my best,’ I can picture him saying. And he is. There are many loving farmers trapped inside really badly designed systems. We all are.

Is there such a thing as a good system? This is something Lauren Gitlin’s MILK piece on goat farming deals with explicitly. Even in a small, artisanal operation where each goat has a name and its needs are tended to with care, Lauren must still be their master. This includes mastering their reproductive capacities. In reckoning with her own decision to remain childfree, when choosing to initiate the goats’ breeding season, she asks: “When will I decide, as the hand of God, to start the clock?” The question of whether we should play God cuts to the heart of eternal dilemmas relating to relations in the Anthropocene, and to many moral quandaries we at Feminist Food Journal wrestle with ourselves. (These quandaries play out in real time; earlier this year, someone commented on one of our food reels on Instagram: “I would like to make the statement that you cannot be feminist and eat eggs. You cannot be feminist and eat dairy. 🙏🏻”. ) As animal geographer Christopher Bear puts it: “The relationship between caring, controlling, and killing is always in tension.”

Queer mylks and feminizing soy

Another theme that echoes across MILK and Milk, From Ground to Glass are constructions of “real” (i.e., cow’s) milk as pure, and others as deviant. In The Myth of Feminizing Soy, Julia Norza, remembers her health-conscious mom swapping soy for cow due to its potentially feminising capacities. She looks at how drinking cow’s milk — and the transformation of contrarian consumers into “soy boys” — has formed part of a neoconservative “return to tradition” movement seeking to strip rights from trans women like her. SOURCED and Wellcome Collection Stories piece Queer cafés and gay mylk by Holly Regan looks at how alternative drink choices can come to represent minoritised communities. As she writes:

Once you’ve realised that you aren’t who you thought you were, interrogating everything from who you love to the biology you were born into, it’s not much of a stretch to switch to tofu.

Accordingly, TikTok has declared that “oat milk is gay”, and in-jokes claim that someone’s drink order becomes a way to determine if they will reciprocate your queer crush.

Something about alternatives to industrial dairy seems to put women and LGBTQ2+ communities at the forefront of the conversation. In MILK, Conversations on Women and Cheese, describes women cheesemongers working together against the co-optation of the dairy industry by patriarchal and capitalist models. In The Future of Cultivated Milk, Ingrid L. Taylor looks at how women biotech entrepreneurs are leading the way to develop cell-cultured milks — replacements for both animal and human — that no longer depend on mammalian breasts. We weren’t quite sure what to make of this topic in February 2022; we’re generally skeptical of technological solutions to systemic problems (essentially, every ism you can name) that intertwine on the issue of dairy and breastfeeding. And we aren’t quite sure what to make of it now. If oat milk is a grassroots café with rainbow flags behind the bar frequented by “a moustachioed person in round spectacles and a perfectly poised beret” who might even make their own version at home, cultivated milk is a brightly-lit, sanitized board room full of angel investors. It remains to be seen whether it will mobilize the same type of alternative politics or come to represent the same undoing of entrenched power structures (although the trajectory of alternative meats does not bode well for these outcomes). We’re particularly interested to see what happens when precision-fermentation companies launch products like yoghurt and cheese — categories where animal-based dairy still reigns supreme.

Milk and nation-making

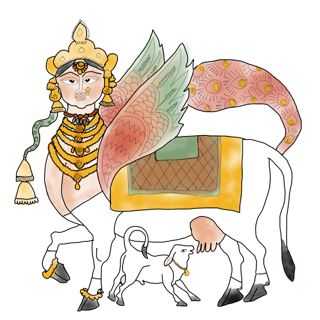

Finally, both issues reminded us that people who make milk are bound up in much larger projects than themselves. In MILK, Adhiambo Edith Magak tells a story of the goddess Isis’ divine breastmilk, a symbol of life and salvation for ancient Egyptians and Nubians alike. (Breast milk was a topic we wished we could’ve dug into more, having received fascinating pitches on wet nursing, formula and neocolonialism, and 17th-century medical norms).

Apoorva Sripathi, writing in both the MILK issue and Milk, from ground to glass explores how in modern times, milk, and its historical ties to conceptions of superiority and strength, has become a tool for nation-making in India, where Western imposition combined with the divinity of the bovine in Hinduism has led to milk being promoted as “not just a food” but “ambrosia itself”. In her MILK piece, she explores how women and cows bear the brunt of rationalizing a Hindu nationalist nation: namely, the veneration of the cow as the “vulnerable” mother that requires protection from so-called “predatory” beings who consume its meat, the control of women’s bodies and reproductive choices. A fascinating addition in her piece for Milk, from ground to glass is that the promotion of milk as a “pure” food from the divine bovine is irrational in the face of eschewing more nutrient-dense animal-sourced foods like eggs. Hindu religious groups have pushed for these to be left off school menus, framing them as unclean, impure, and taboo. Milk can make a vegetarian nation but eggs cannot; Apoorva argues that this dogma is to the detriment of the nation’s nutrition and to the benefit of Hindu casteist ideologies.

It’s been a joy to reflect on MILK and engage with so many new pieces on the subject. Like in 2022, we’re still thinking about how to manifest a feminist milk paradigm, and we hope that this newsletter has given you some ideas, too. We’d love to continue the conversation on our Substack.

Isabela Vera and Zoë Johnson are founding editors of Feminist Food Journal.

Further reading

Taylor, A. & Taylor, T. (2022). Our Animals, Ourselves: The Socialist Feminist Case for Animal Liberation. Lux Magazine.

Stănescu, V. (2018). ‘White Power Milk’: Milk, Dietary Racism, and the ‘Alt-Right’, Animal Studies Journal, 7(2), 103-128.

Soy Boys, Maintenance Phase (podcast)