SOURCED in conversation with Alicia Kennedy

Reserve your space at our first event for 2024! It is online and free, with limited spaces.

On Wednesday 15 May, 7pm GMT we will be hosting our first event of 2024. It will be online, and free, but we do have limited (zoom restricted) space so please sign up!

We will speaking with Alicia Kennedy, who we at Sourced are a huge fan of! We will be discussing Alicia’s book, her current work, and ways of thinking about sourcing.

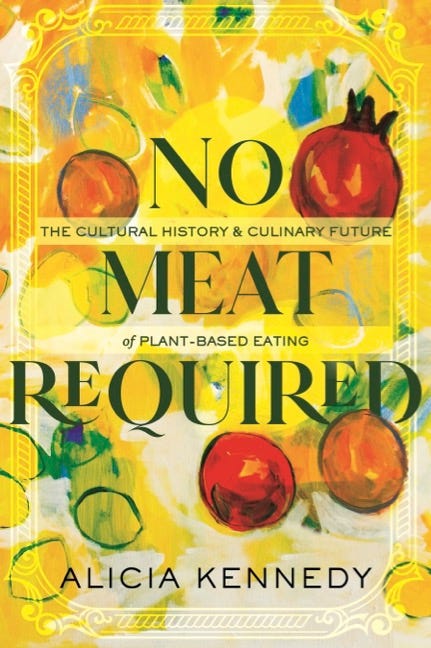

Alicia Kennedy is a food and culture writer from Long Island. She writes the weekly newsletter From the Desk of Alicia Kennedy, and is the author of No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating and the forthcoming On Eating: The Making and Unmaking of My Appetites.

Below we have an extract from her book No Meat Required, to whet your appetite.

But first, a few other pieces of event news:

Sourced's postcard tour of Canaletto

Wednesday 12 June, for members of the National Portrait Gallery will be able to have a guided tour of Canaletto’s painting and they became toursit postcards of the day, and the impact of Venice on food trade systems to Europe – led by Sourced founders Dr Anna Sulan Masing and Chloe-Rse Crabtree.

There is still time to become a member, to join in this tour as well as all the other great benefits.

Mixed up supper club

To celebrate Emma Slade Edmondson & Nicole Ocran’s debut book The Half Of It, they are recording an episode of their podcast, Mixed Up, live with Sourced founder Anna Sulan Masing as guest, followed by (Sourced favourtie!) chef Ana da Costa cooking up a storm. This will be a wonderful evening!

And finally, a little reminder that we are reader-funded publication. All the pieces we commission are available for free on our website, and contributors are paid by subscriptions to our Substack newsletter. We you are able to, we really appreciate your support.

With Tree Season we have been thinking about landscape - what landscapes do we want to live in, do we want to create, and how do we go about creating landscapse and environments that will nourish us in multiple ways? This first chapter of Alicia’s book asks the question about the planet, and linking what we eat to the planet we live in and the various spaces and identities that planet holds. This last part of the chapter addresses the idea of place and connectivity of space and people and eating – fundemental ideas to think about before we start tackling the question of what we want to build.

Excerpt from No Meat Required: the cultural history & culinary future of plant-based eating, from the chapter ‘Diet for whose planet?’:

Most studies put transport at only 10 percent of total emissions of the foods consumed in US households, which leads folks like Washington Post columnist Tamar Haspel to declare, “LOCAL FOODS AREN’T BETTER FOR THE CLIMATE!” Pieces in online news and opinion outlets Vox and Noema echo this sentiment against localism, focusing solely on an efficiency in long-distance food transport that discounts a lot of significant effects of becoming en- gaged in local agriculture and its potential resilience during catastro- phe. Yes, the emissions are mainly happening in production. The most important thing is what you’re eating and how it was grown—of course, beans are preferred to beef, even if the beef came from a farm down the street—but how far it traveled? Doesn’t matter.

It matters, though, for things such as local economies, the main- tenance of cultural tradition and regional foodways, and the simple matter of the sense of community that comes from going to the farmers’ market or knowing that the apples you picked up at a gro- cery store didn’t spend days or weeks on a truck or ship. Here in Puerto Rico, where famously 85 percent of food is imported, why would I want onions from California that are already going moldy in the grocery store when I can get flavorful, fresh ones by supporting a local farmer?Or buy imported eggs in a supermarket instead of local ones, whose prices aren’t as affected by global inflation? Numbers aren’t all that matter when we’re talking about the food system, because the quality of the ingredients we’re cooking with and the good feeling of talking to the person who grew those ingredients aren’t really quantifiable.

Why wouldn’t we want to move toward smaller farms and priori- tizing local economies? I would prefer to buy my pens from my local pharmacy than order them on Amazon, because one of these contrib- utes to my neighborhood and the other union-busts and underpays its own employees, who’ve worked hard enough over the years to help the founder Jeff Bezos fly to space for some reason. The same principle stands when it comes to food: Why would I support massive agricultural and biotech conglomerates who underpay workers and also don’t pay the real environmental cost of their pesticide-heavy, monocrop practices instead of supporting my local community?

Vandana Shiva, in Mold magazine, said, “Abundance is where the seed and the food are interconnected again. Instead of eating 10,000 kinds of plants appropriate to place, and creating living economies appropriate to place, we made eating the ultimate act of alienation from the earth.” “Appropriate to place” is the key phrase here, which is precisely why it’s a terrible though predictable fact that the local food movement in the US has been made into a bourgeois joke.

Food-policy journalist Lisa Held took this idea to task in her newsletter Peeled, writing, “In the face of dire climate predictions, it can be tempting to rank straight emissions above all other concerns, but saying that local food is ‘not better for the climate’ solely on the basis that there’s no definitive proof that miles matter much, without considering any other factors, is jumping to a conclusion.”

A food product’s significance and impact have to be determined in the aggregate, by looking at how they’re affecting the health of not just the soil and surrounding water but the workers toiling to bring it to people’s tables. As Held concludes, farms that work on a smaller scale to sell to their local markets are going to minimize poor environmental and human effects by the very virtue of their work. If you’re not trying to feed the whole country, you’re not going to produce at a scale that creates waste, taxes the soil, uses excessive water, or gets packaged in plastic and Styrofoam to make long trips while remaining intact.

I return egg cartons and plastic pint containers for cherry tomatoes to our farmers’ market each week, because I know they’ll be reused. I use any plastic produce bags to pick up dog poop. These are the rhythm of my week, in sync with my market. Do I sound elitist for these practices?

For some reason, Lappé was excellent at conveying her points without alienating people—she was inviting; she was rooted in fact and not aesthetics. This is her legacy: shifting the food narrative for the white middle class.

But the farm-to-table movement that emerged in the early twenty-first century was swiftly slapped down as elitist. Its “high priests,” as a 2013 op-ed by Henry I. Miller and Jayson Lusk referred to them, were Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, chef and activist Alice Waters of Berkeley’s Chez Panisse, and writer Mark Bittman. Miller and Lusk’s op-ed comes from a free-market perspective in which all that really matters is the efficiency and cost of production; ecological concerns aren’t a factor, and if local produce really does taste better, then it should have no problem selling at a high, unsubsidized cost.

By anointing “high priests” and priestesses who all looked and sounded quite similar to each other, the media easily made a mockery of the food movement in the United States. While the 1970s seemed full of hope, the lack of a big, broad, diverse coalition to keep pressure on the government has meant taxpayer money subsidizes industrial meat and dairy at a rate of $38 billion per year. During the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly sixty thousand cases were traced back to meatpacking workers in unsafe conditions. When a fake news story went viral about President Joe Biden limiting people’s beef consumption to four pounds per year, there was outrage on the part of omnivores, who posted gigantic steaks on social media in protest. All of this could make a person very pessimistic.

At this crucial moment in the life of this planet, though, there is no time for that. We’ve known—all these people have known and do know—that the Global North sucks resources from the Global South, deforests it, demands cheap goods from it, and that fight has only become more fierce with the experience of a global pandemic. Here could be where we change, where we radically alter our rela- tionship to fossil fuels and mindless consumption. First, though, we need to understand how meat came to obtain its vaunted status, its platinum-standard cultural capital, to the point that it is destroying the planet. Then we’ll get back to how people have tried and are trying to change that.