SOURCED: Lets get started.

For this first paid-subscriber newsletter, enjoy the treat of a few reading recommendations and some content from our founders. Anna talks about what decolonising means to her and about the whisky she’s drunk this week. Chloe shares thoughts on mid-century salads and food media.

Decolonising, a conversation

Anna Sulan Masing

Decolonising is a conversation, conversations. To me, it isn’t An Act, but actions. It involves continuous, every day, consistent, shifts, shifting, thinking, re-thinking, listening. It is both hard work and incredibly easy. It is a small step in a new direction that leads you down a whole new road, a cliched analogy but it works. The work of decolonising is listening to and looking for narratives beyond the norm.

In an interview with Alicia Kennedy for her newsletter I said that a small shift in a sentence of a story (about the history of America) could open up a whole set of questions and re-centre the story of the US on indigenous people. Being open to those questions and pursuing them, that is the hard part.

There has been a lot of talk in the last few months about decolonising various parts of our [Global North] lives, such as ‘decolonising bookshelves’ – buying books about race, colonialism, and power. This is an act. The action is of course to do the reading and to be able to sit with your uncomfortableness as the questions build up inside you. To do the work of decolonising, for me, has always been about re-thinking narratives of space and anchoring the work to the physical; this is both seeing how it plays out in real life but also relating it to place.

Relating the work to land; or rather to soil, to earth, to the space we place our feet is where I see the deep work of decolonising begins. If you google ‘land’, the first page is full of ‘land for sale’, registering land with the government and property searches – the dominant notion of ‘land’ is tied to a colonial idea of soil centred on ownership.

“The process of decolonisation or of postcolonial development and politics becomes a (re)establishment of indigenous geographical identity, which is not an “authentic” reality in need of uncovering (such an assumption would support the tourist narratives of an exotic and primitive native and her land), but a (re)vitalizaing of indigenous geographic identity through knowledges of and relationships with place”

- Karen Amimoto Igersoll, Waves of Knowing.

Igersoll’s book is about regaining ownership of surfing in Hawai’i and she emphasises her message toward current action and why emphasis is placed on the prefix, ‘re’. She talks about this idea of ‘re’ because decolonising is to look to the past - as the knowledge has always been there - but to do it without nostalgia, and so it is about creating new-ness too - “…a process of (re)creation through both historical memories of, and modern engagement with, the seascape. [It is an] enactment that connects the history of Hawai’i”. This work is about a reclaiming and decolonising the national identity of Hawai’i.

My PhD research looked at postcolonial spaces and part of the research – although didn’t make it into my thesis, it was embedded in the thinking – was about how postcolonial states redefine their [national] identity. So much of that work was about decolonisation if these states wanted to create spaces of equality; the thing is of course, that a lot of states don’t do that work because the colonial structures of power are very enticing and/or the colonialists never left (America, Canada, New Zealand, Australia…).

I looked at this idea of ‘re’ through cooking in my PhD research, as a way to value the work of women as creative work. Migrant women cook to build home, to coat new spaces in scents and to nourish their loved ones; to give them power, to take up space, to be seen. This repetitive task of daily cooking needs to be seen as a constantly creative action, building and re-building identity and belonging, but it is not often seen as such because it doesn't have production (financial) value attached to it. Migrant women in postcolonial spaces are women facing a new national space, women who have moved from rural spaces to urban and/or the women of indigenous communities finding their spaces have been taken from them. And of course, this work happens in the Global North by migrant women of the Global South. Since my PhD I have continued to interview, platform and work with women of migrant and diaspora communities through my food writing and projects.

So what does decolonising look like in the food and drinks world?

In my upcoming interview with Ryan Chetiyawardana, Ryan talks about how bartenders are re-thinking what a cocktail is, moving away from formulas that have dominated the industry for decades (centuries!?); this is decolonising the bar world. Ryan talks about how a lot of this inspiration is coming from places such as Singapore - the interview will be live on Monday 17 August on SOURCED.

A conversation I have been having with Jonathan Nunn, and was discussed on Sunday’s Black Book talks, is the colonial approach to restaurant reviews and criticism. To me, this is around the structure of the writing and the use of language and tone such as ‘discovery’, which - when the restaurants in question are minority-owned - is uncomfortable and leans into narratives of exoticism. Sign up to Nunn’s Vittles paid newsletter, where this week he will be writing about this in detail.

Narratives are systems of knowledge, and knowledge is an ingredient. If we are to create equitable culinary systems we need to understand how knowledge travels – we need to understand what decolonising means to us, and we need to decolonise our knowledge and our narratives. So the question I want to ask readers is to look up the history of distilling – how many different stories of origin can you find and where does the journey of that knowledge travel?

Salad Days

Chloe-Rose Crabtree

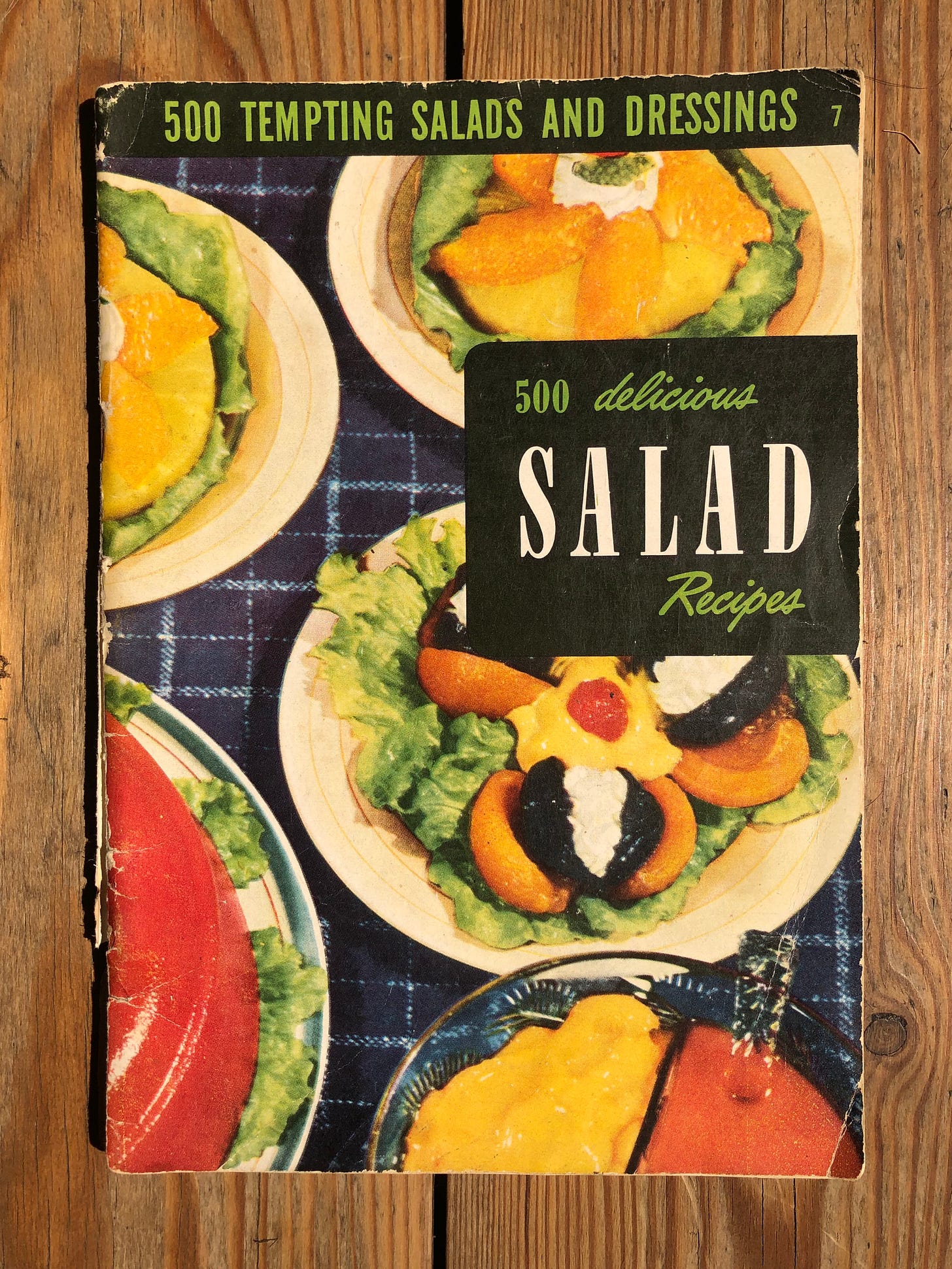

As a Californian, I am roughly 60% salad. This is probably why this little pamphlet of salad recipes (500!) has charmed me since it was gifted to me a few years back.

I fully intended to make a moulded Jell-O salad for this newsletter issue. I had already prepared myself for the specific horror of making, setting, slicing and eating shrimp cocktail in loaf form. Lucky for my dinner plans, the internet (ok, an Instagram poll with 10 responses) decided it was more interested in this indecipherable photo from a book boasting ‘the most magnificent collection of food pictures ever brought together between covers.’

After 20 minutes scrutinizing the various shades of grey and only being able to decipher some salami slices and what could be baby gem leaves, I realised what captivated me about this book was its specific brand of accessibility, and what it can tell us about our relationship to food media today.

The pamphlet’s editorial team were able to fit all 500 recipes in a 48-page booklet by including recipes with innumerable permutations. The avocado salad I made for our first live tutorial suggested at least four different dressings, and three different arrangements. These recipes offer the reader a sense of accessibility through the knowledge that ingredients can be easily swapped or substituted.

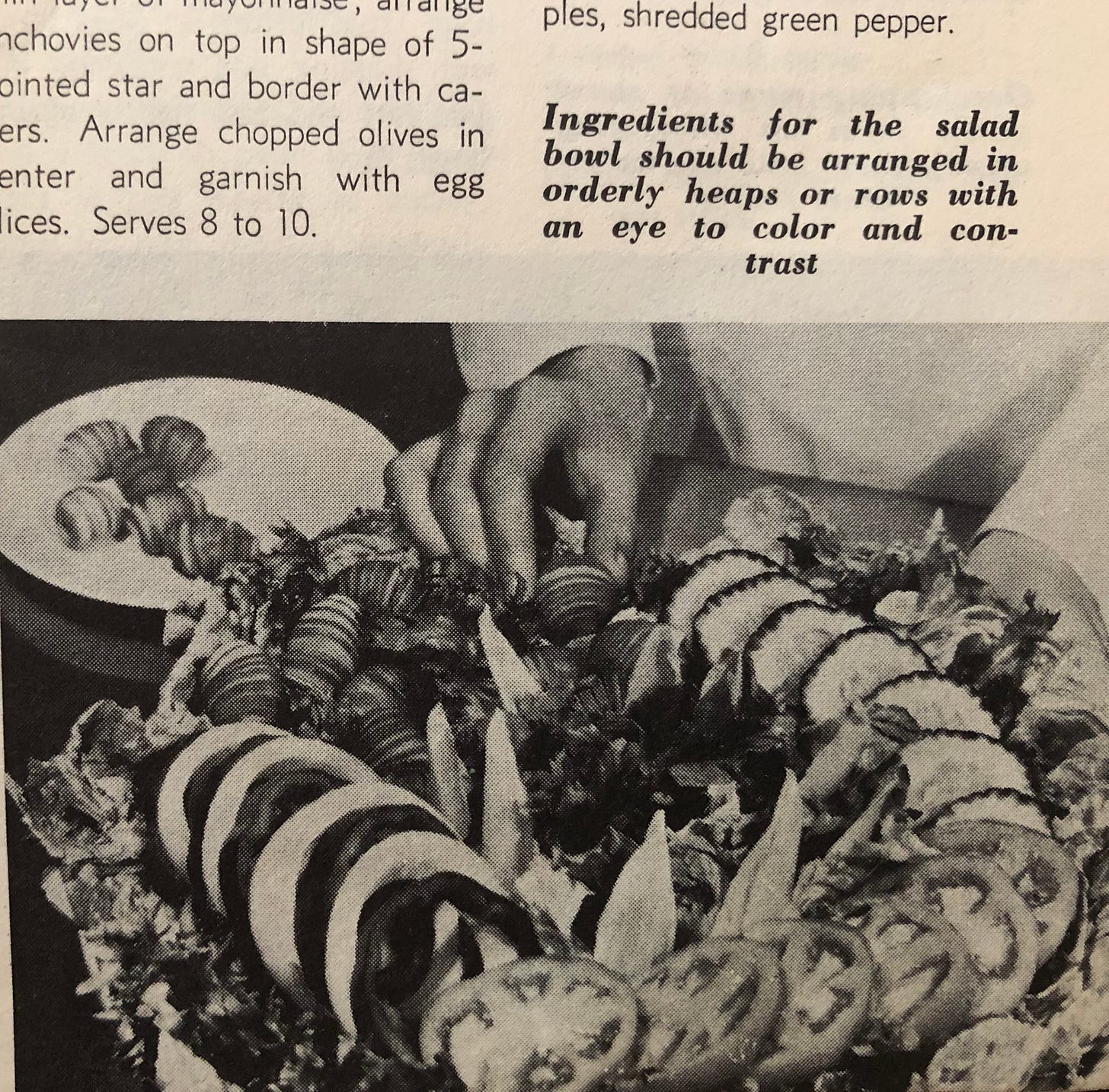

Published in 1954, ‘500 Delicious Salad Recipes’ was Issue 7 of 24 from the Encyclopedia of Cooking issued by Chicago’s former Culinary Arts Institute. But, as with most of the institutional cookbooks and domestic guides I read for my thesis research, the recipes in these pamphlets are really secondary information, serving suggestions. The photos are rarely captioned with the recipe they’re meant to depict, rather they become places for the editorial team to demonstrate the serving aesthetic a hostess should aim to emulate. Flavour combinations are secondary to visual presentation and the food transforms from sustenance to performance.

While other pamphlets focusing on ‘Leftovers’ or ‘Meals for Children’ might be more economically minded in their instruction, the salad pamphlet is particularly interesting as a piece of food history because it assumes a few things about the reader:

The reader is a woman who sees herself as a ‘hostess’

The reader has easy access to a variety of fresh produce

The reader has space to store fresh produce (i.e. refrigeration)

At the time of the Encylopedia’s publication, the average American household income was $4,500 annually. A refrigerator could cost as much as a full month’s salary for the average home. This pamphlet gives the illusion that its recipes are easily approachable but the lifestyle portrayed in its pages is mostly aspirational.

Apart from a 12-year old article in a local Chicago paper, I could find very little about the former Culinary Arts Institute and its director Ruth Berolzheimer (1886-1965). Along with editing the Encyclopedia of Cooking, Berolzheimer was also author of a variety of American cookbooks aimed at an audience of middle class housewives. Her work is an extension of the progressive movement led by educated middle-class women at the turn of the 20th century– a group of women I like to call proto-influencers.

Women like Berolzheimer worked with food, not because they had a particular love for it, but because it was a venue of expertise open to them. Schools like the Culinary Arts Institute were created as an acceptable space for women to gain higher education in matters of science, economy and policy, so long as it related to matters of domesticity.

As professionals, these women were ‘domestic scientists’ and authority figures when it came to how people understood the economy, health and morality of the American home – there are parallels to this history in other countries as well, especially in the UK. Their work was sometimes published in academic journals, but was more widely circulated through women’s magazines, lifestyle columns, cookbooks and pamphlets. These are the voices that built food media and their vision of ‘food culture’ was tied to an idea that there is a way food should be enjoyed.

Our idea of dinner party fare may have moved past jellied salads or mayo-heavy appetisers, but the idea that there’s something you’re ‘supposed’ to do with food still dictates a lot of how we engage with food culture. Does fruit belong in a salad? Do we serve the cheese course before or after dessert? Wine with sediment is good now, right?

All of this is a really long way of saying that I could not for the life of me figure out what was in that photo. But here my attempted recreation, and a recipe for a potato salad I made to go with some on-offer lamb cutlets:

Herbed Yogurt Potato Salad

Serves 4 as a side

1 kg potato, medium-dice

Dressing

1 red onion, small-dice

3 sprigs dill, chopped

4 springs mint, chopped

1 c (225 ml) yogurt

¼ c (75ml) creme fraiche or sour cream

¼ tsp (large dash) cayenne pepper

Large spoonful of dijon or other strong mustard

Juice from 1 lemon

2 tbs (large glug) apple cider vinegar, or vinegar of your choice

2 tbs (large glug) olive oil

Salt and pepper to taste

Boil your potatoes in salty water for 15-20 minutes, or until fork-tender. Drain and cool with an ice bath or cold water. Sprinkle potatoes with large-flake salt and toss briefly - little cuts in the potato will help them take in the dressing flavor. Mix dressing ingredients together and toss over potatoes, adjust seasoning to taste. Let sit for 30 minutes before serving. Arrange as desired on plates or eat straight from the bowl. Will keep in the fridge for 4 days.

What Anna drank this week:

Nikka Days as a highball with ice and soda

Nikka is a Japanese whisky and the story (at least on its English language website) is centred on how the founder, Masataka Taketsur, was the first Japanese man to go to Scotland to learn how to make whisky. But, he comes from a sake brewing family – I am more curious at how that heritage influenced his approach to making whisky. Is centring his, and the distillery’s, story on Scotland a way to legitimise the brand? Are we able to move away from relating the making of certain booze to its European counterparts? Brands need to start decolonising their marketing...

Peated Westland a dram with a tiny bit of ice as it was VERY HOT day

From Seattle, this whisky is made partly from ”heavily peated malt from Scotland” I found this interesting as I think of whisky (and most spirits!) as being a reflection of place and many brands in the American Single Malt category speak of the American-ness of their product, which includes produce such as the malt. I spoke to a whiskey friend who suggested that a sense of place could be heritage (and any Single Malt looks to Scotland, of course) and that you can imbue ‘place’ through the aging process. But still, I am curious as to why they wanted to transport this malt? Is this a creative exercise? Or a way to bind (legitimise?) the connection to origins of single malt? What do the peat flavours have to do with Washington State? And, broadly how does flavour play into ideas of place and identity?

Recommended readings

Anna -

I want to recommend the book Letters to Young Farmers, it is a small book packed with essays from farmers, food people, academics. I read a quote out in our tutorial by Mas Masumoto, which to me explained how culinary systems are about time - how time occupies multiple spaces, the past is with us in the present and in the future. “Repetition is the natural rhythm of farming. [...] Your grandfather left his fingerprints all over this land. The hardpan rock piles along a ditch back. The welded seams on old equipment that hold fasts after decades…” To me also, this non linear thinking of space and time is a decolonisation, as it places value outside of product and back into nature and people.

Chloe-

In my tangential research into refrigeration and the American home this week, I came across Fresh: A Perishable History by Susanne Elizabeth Freidberg. I only had a chance to glance at the preview but I am very intrigued by the relationship drawn between getting refrigerators into American homes and the commercial interests of ice manufacturers. I also really enjoyed this week’s edition of Half and Half by Rachel Krishna where she explores the idea of authenticity and the inauthentic-nature of its pursuit.